The positive effects of reducing caloric intake on age-related pathologies in mammals, and particularly primates, remain controversial. The mouse lemur, a lower primate, has a life expectancy of about 12 years, making it an excellent model for studies on aging. Additionally, mouse lemurs and humans have numerous physiological similarities.

A ten-year study headed by the National Center for Scientific Research and the National Natural History Museum confirmed that the benefits of caloric restriction observed in short-lifespan animals (worms, flies, mice) held for mouse lemurs as well.

In that study, which benefited from the participation of the François Jacob Institute of Biology among others, a group of mouse lemurs was subjected to moderate, chronic caloric restriction (30% less calories than the control group) from adulthood to death (Restrikal cohort, see figure below). The researchers considered survival data and any possible age-related health or cognitive variations. The first results at ten years showed that the Restrikal cohort benefited from a 50% increase in longevity compared to the control group. More precisely, median survival was 9.6 years in the Restrikal group vs. 6.4 years in the control group. Thereafter, and for the first time in primates, the researchers showed an increase in maximal lifespan, with more than a third of the calorically-restricted lemurs still alive at the death of the last control lemur at 11.3 years.

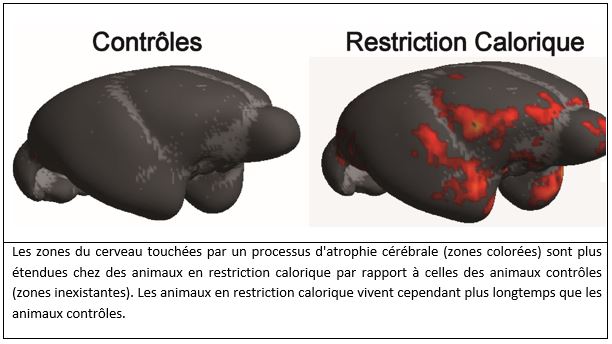

In addition to living longer, the Restrikal group presented a lower incidence of habitually age-related diseases such as cancer or diabetes, and had the morphological characteristics of younger animals. Imaging studies on the brains of the very old animals showed that the Restrikal group had a significant decrease in atrophy of white matter (the neural fibers connecting different brain regions) but also an increase in atrophy of gray matter (the neuronal cellular bodies). The gray matter loss was a mystery for the researchers, but without consequence on the motor and cognitive capacities of the animals.

These results strongly suggest that constant caloric restriction is currently the most effective way to extend the maximum lifespan of and slow the aging process in a non-human primate. The researchers will now turn their attention to associating caloric restriction with a second parameter, such as physical exercise, in an attempt to push the limits of longevity even further.